By Chris Benedict

By Chris Benedict

Of the countless films which Roscoe Arbuckle and Charlie Chaplin would plow through during their tenures at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios (Chaplin’s being of a mere 10-month duration), in only seven of them-between March 2 and September 7, 1914-would they appear together. Only the last, their hilarious drunken carousal in “The Rounders”, can be considered an equitable collaboration. Begrudgingly billed and still remembered as “Fatty” as well as overshadowed by the enduring legacy of Chaplin’s Little Tramp, it is sadly lost on many contemporary movie lovers what a pioneering comedic genius Roscoe Arbuckle was, not to mention one of cinema’s first truly beloved superstars. He mentored both Chaplin and Buster Keaton and it should go without saying that Chris Farley, John Belushi, and Jackie Gleason are a few who owed tremendous debts of gratitude to Roscoe.

Literally cranking out one or two-reelers (which would run anywhere from a couple of minutes to just under half an hour) at breakneck speed, Keystone’s filmmaking ensemble was capable of producing (mostly) quality moving pictures several times a week in some instances. During the salad days of slapstick comedy (from the early teens to late 1920s), you would think that prizefighting would have been ripe for parody. However, despite the fact that many screen luminaries of the day (not unlike any other era) were fight fans, boxing was surprisingly seldom played for laughs. Chaplin would revisit pugilistic themes in 1915’s “The Champion” for Essanay Studios and, to a lesser degree, his 1931 masterpiece “City Lights”. The best known example is arguably Buster Keaton’s feature-length “Battling Butler” from 1926. Arbuckle’s latest starring vehicle was a 27-minute short which went before the cameras under the working title “A Fighting Demon”, but would be released on June 11, 1914 as “The Knockout” after that name became available when it was swapped with “The Fatal Mallet” for Charlie Chaplin’s previous release ten days earlier.

Roscoe’s character Pug emerges from a restaurant sharing his lunch with his pet pit-bull terrier and frequent co-star Luke. Beckoned by his beautiful girlfriend (Roscoe’s real-life wife Minta Durfee), Pug tosses his sandwich aside but is denied a kiss on the lips. Instead, she demurely plants one on his cheek from where Arbuckle, in a variation of one of his favorite bits of business, pretends to peel it off and place on his mouth while mugging for the camera with love-struck googly-eyes. Meanwhile, two hobos unable to afford a meal of their own take notice of a sign posted outside of the music hall advertising “Cyclone Flynn Meets All Comers-Winner Takes All”. One of the hungry bums, portrayed by Hank Mann, who would also play the credited role of ‘A Prizefighter’ in the boxing scene of Chaplin’s “City Lights” and was said to have originated the idea for the Keystone Kops, takes it upon himself to impersonate Cyclone with the hope of obtaining the purse money.

Pug’s rival-Arbuckle’s nephew Al St. John, a Keystone player who would later gain renown in the role of Fuzzy Q. Jones in over 80 Westerns-makes a pass at Minta while she waits for Roscoe’s character outside of a cigar store. An altercation naturally ensues, involving bricks being hurled at the considerable target provided by Pug-all to no effect-and ending with Al and his three cohorts dumped inside a watering trough. After making amends with a handshake in front of the music hall, Al entertains the notion of entering Pug into the boxing exhibition against Cyclone Flynn and has him pass a scrawled note to the promoter boasting “I’ll take up your fight proposition, and believe me, there’ll be plenty of fight. Pug.”

The Dingville Athletic Club is where Pug will commence his short-time training and Roscoe will again break the cinematic fourth wall between actor and audience as he is so fond of doing. In a gag he will repeat in the 1917 short “Coney Island” with Buster Keaton, Arbuckle’s character undoes his suspenders and loosens his trousers before coquettishly urging the camera up to chest-level so that he may change into his boxing attire with some semblance of privacy, before panning back down to reveal shorts worn over a pair of long-johns. Pug gets the better of a comical exchange with a boxing dummy, easily lifts a 500-lb weight overhead with one hand, and breaks a steel chain in two over his neck to the delight of Al and the gang.

Cyclone Flynn arrives by rail at the Dingville station, disembarking and itching for a fight. Discovering his transient impostor, Flynn floors him outside the music hall with a single punch. Standing 6-foot-1 and weighing then in the neighborhood of 200 pounds, Edgar Kennedy was a natural choice to play Cyclone especially seeing as though he had gone from the vaudeville stage to the boxing ring as a young man, winning the Pacific Coast Amateur Heavyweight Championship at 21 and proudly showing the commemorative prize watch to anyone who would sit still long enough to listen to stories of his fistic prowess which, as Kennedy liked to tell it, included once sparring fifteen rounds with Jack Dempsey. Of the 500 films Edgar would make during his career, one would be “Daredevil Jack”, a 1920 action film serial starring Dempsey, who was the reigning heavyweight champion, and featuring “Man of a Thousand Faces” Lon Chaney in a small supporting part. “Jack is a fine fellow, but he doesn’t know how to pull a punch,” Kennedy said in a retrospective interview with the Milwaukee Journal. “I took some awful pummelings. But Dempsey never did knock me out really; even though I had to fall on the floor, I did it under my own power. I was always glad to. It meant a nice rest.”

The hobos, found out now by the real Cyclone, decide to covertly appeal to Pug’s naiveté and throw over the gym wall a balled up wad of paper, passed off as half threat/half overture on behalf of the boxer, which reads, “It’s very unpleasant knocking out fat men, so lay down and we’ll go halvers on the coin.” Arbuckle rips it up and goes along his merry way, punching out Al and his associates while exiting the gym just for the fun of it. Minta must dress like a man to gain admittance to the fight where she uneasily sits ringside among dozens of rowdy spectators, one of which is Keystone founder, actor, and director Mack Sennett himself. Pug is stopped outside the stage door by an intimidating gambler (Mack Swain, one half of the comedy duo Ambrose and Walrus with Chester Conklin and memorable as the foil in future Charlie Chaplin films) who brandishes a gun to compliment his not terribly subtle verbal warning, “I’m betting heavy on you, so win or I’ll kill you.”

Referee Charlie Chaplin makes a grand entrance with a pratfall between the ropes and into the ring, rising to slap Roscoe across the back as he chugs milk from a bottle in his corner, resulting in a classic spit take. Arbuckle not only exhibited a lack of animosity, professional jealousy, or fear of being upstaged by younger actors like Chaplin and Keaton, he was in fact extremely generous with his time and insights, offering guidance and assisting them in creating scene-stealing sight gags. Pug and Cyclone Flynn wrestle and throw the occasional punch, most of which catch Chaplin as he flits about, and a retaliatory kick in the seat of his pants from Chaplin sends Pug to the canvas while Charlie commences the count. Arbuckle cowers in the corner as Cyclone pummels both him and Chaplin then takes a spontaneous milk break which spews all over the crowd after he is hit from behind by Flynn. Pug and Chaplin become entangled and wail away at one another as they spin in concentric circles like a dog chasing its tail. Between rounds, Al St. John spits water in Pug’s face while the other handlers frantically wave towels to resuscitate the winded fighter. Arbuckle and Chaplin both slip in the excess water once hostilities resume, Charlie sliding along the ring on his backside by using the bottom rope as a sort of pulley. Cyclone clobbers Pug to the footlights with a right hand to the back of the head and, after once more beating Chaplin’s count, Roscoe pulls two pistols from the pockets of the gambler who is seated in a private box to stage right.

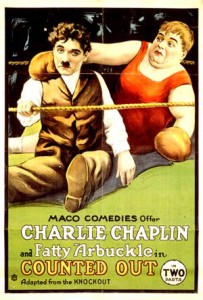

Despite still wearing his boxing gloves, Pug begins blasting away, clearing the hall and chasing Cyclone up a telephone pole and across rooftops with the Keystone Kops now in hot pursuit. They manage to lasso Roscoe but he effortlessly drags them behind him through the streets and onto a boardwalk from which he leaps into the river, taking the still-tethered Kops with him. The movie, as with some of Keystone’s more slapdash efforts, ends abruptly and with no character or plot resolution. However, while it may not necessarily qualify as the best, “The Knockout” does appear to have been the first pugilistic comedy-if, that is, you discount Thomas Edison’s 1894 experiment “Boxing Cats” and the 1895 German-produced “Boxing Kangaroo”, both running less than 20 seconds in length and being exactly what you would expect judging by title alone. Depending on the source you consult, directorial duties of “The Knockout” are attributed to Charles Avery (one of the original seven Keystone Kops who directed several other Arbuckle shorts), Mack Sennett, or Roscoe himself. It would be re-issued in 1918 as “The Pugilist” and again in 1920 under the title “Counted Out” (much later home video releases would give it the names “In Training” or “In the Ring”) which bestow top billing to Chaplin over Arbuckle regardless of Charlie’s minimal screen time. And this slight even predates the lurid 1921 Labor Day weekend sex scandal which would ruin Roscoe personally, professionally, and financially despite an acquittal in the third criminal trial stemming from charges of rape and manslaughter in the death of actress Virginia Rappe during a party in Arbuckle’s room at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel.

His reputation and very name dragged through the proverbial mud, the proven-innocent but still reviled Arbuckle would be permitted to direct only a handful of films either without credit or under the pseudonym William Goodrich before his premature death in 1933. Among the few who vouched for his character, with no second thought given to any personal ramifications, were Roscoe’s friends and former protégés Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, standing defiantly in his corner the way every down-and-out fighter needs some faithful supporters.

Coming Soon: Charlie Chaplin Returns To An NewzBreaker Screen Near You In His 1915 Boxing Comedy “The Champion”. Stay Tuned…

[si-contact-form form=’3′]

August 30th, 2015

August 30th, 2015  CEO

CEO  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: