We all maintain unique perspectives as to what we find aesthetically pleasurable or distasteful, repugnant or elegant, entertain our own preferences, predilections, or perversions. How easily and readily this thought process can be bifurcated is shameful, leaving no middle ground or grey area in which to challenge or overturn the societal standards which are far too often accepted literally at face value, treated and revered like holy scripture as though to discourage any further discussion, debate, or compromise.

Beauty, without question, is in the eye of the beholder. A trite but true sentiment which has made its way through the millennia in varying florid declarations but believed to date back to Greece in the 3rd Century BC. Beginning in 1959, Rod Serling would pull back the veil behind which lay hidden a fifth dimension-one of sound, sight, and mind-wherein he maneuvered uniquely unforgettable characters through the baser instincts of the human condition, reversing the mirror we collectively view ourselves through so that we as a society were forced to withstand the sight of the dark side of our own souls, turning long-held cultural conventions upside-down and inside-out.

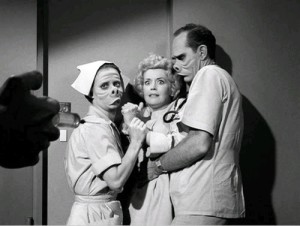

In the 1960 second season episode “Eye of the Beholder”, Janet Tyler has undergone her eleventh surgical experiment (the state-mandated limit) in an attempt to appear “normal” and thus avoid having to “congregate with people of her own kind” or, as Janet frets beneath her bandages, become “segregated in a ghetto designed for freaks.” She tells the doctors and nurses-whose faces are all turned off-camera, seen in silhouette, or concealed behind strategically placed objects-of the simple pleasures to be had by wearing a mask, getting a job, sitting outside, seeing the sunshine, feeling the night, and smelling the flowers if not for a state which played god, penalizing people for an accident at birth and making ugliness a crime.

The brilliant trademark Serling twist comes when Janet’s bandages are removed, revealing a striking-looking blonde woman (Donna Douglas, who would go on to play Elly May Clampett on The Beverly Hillbillies) from whom the hospital staff recoil in horror as we, in turn, are finally subjected to the full measure of their grotesquely deformed faces. Janet attempts to escape while a video screen projects a speech being given by The Leader who emphatically sounds the call in a manner reminiscent of Hitler or Stalin of the need for “a single purpose, a single norm, a single approach, a single entity of people, a single virtue, a single morality, a single philosophy of government.” Edson Stroll, also featured in the Twilight Zone episode “The Trade-Ins” as well as two lesser Three Stooges films, portrayed Walter Smith, the handsome man who will escort a hysterical Janet into a community of banished outcasts, promising her the fulfillment of belonging and of love as the mutants of the medical facility look on approvingly and with great pity.

“Now the questions that come to mind…where is this place and when is it?” asks Rod Serling in the program’s epilogue. “What kind of world where ugliness is the norm and beauty the deviation from that norm? You want an answer?” Serling challenges the viewer. “The answer is it doesn’t make any difference. Because the old saying happens to be true. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. In this year or a hundred years hence. On this planet or wherever there is human life, perhaps out amongst the stars.”

I wonder whether we will ever be able to topple the towering structure of ignorance and fear which we foolishly perpetuate and cower behind, allowing us to separate ourselves from one another predicated upon no more feeble a construct than superficial differences real or imagined, engendering juvenile and counter-intuitive finger pointing and name calling, derision, expulsion, or elimination. I wonder how many among us endeavor to strive toward and live in a world like that, where what appears on the surface to be shocking and sensational can inspire adaptations or alterations to firmly entrenched prejudices so that they may begin to unravel and more accurately represent what should instead be simply prosaic and pedestrian. Where we embrace rather than shun the lost causes, hard luck cases, itinerant souls, pariahs, rejects, losers, the likeable but seemingly unusable.

I wonder.

[si-contact-form form=’3′]

September 10th, 2015

September 10th, 2015  CEO

CEO

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: