On February 28th, 2001, WNSW 1430 was preparing to go off the air. Broadcasting from the city of Newark, New Jersey and known by the catchy title of “Sunny 1430,” WNSW was the third and (to this date) last known radio station famous for airing big band and standards music in the New York metropolitan market, the other two being WNEW and its successor WQEW, both of which went off the air in 1992 and 1999, respectively.

In the three years that WNSW worked with the standards format, a steady stream of on-air talent introduced the classic music of Sinatra and his contemporaries to new audiences, including Johnny Knox, Chuck Leonard, legendary Danny Stiles, as well as vocalist Julius LaRosa.

With the format about to switch back to brokered programming, the disc jockey in charge of the last day’s programming chose a song to close out the final evening broadcast, its lyrics signaling not only the end of the standards format, but the end of the station as it was known. The song, appropriately, was a Sinatra tune, one he recorded in the midst of his lifetime, known as “Softly, As I Leave You.”

The recording of “Softly, As I Leave You” marked an interesting turning point in Sinatra’s career. While the Chairman had experimented in embracing new sounds (“Can I Steal A Little Love?” from 1957 is a good example) throughout the better portion of his recording career, “Softly,” laid down on July 17th, 1964, is considered by many Sinatra historians to be the defining moment in which Sinatra began to waver from his usual sound (in both voice and arrangement) for an accompaniment that some have considered a form of soft rock.

The brainchild behind the recording was that of Ernie Freeman, this song being the first orchestration written for Sinatra by the arranger in his catalog. Written by the Italian song team of Giorgio Calabrese and Tony De Vita, “Softly” was later transformed into English by British songwriter Hal Shaper in 1961. Singer Matt Monro, also of the United Kingdom (in fact heralded often as the “British Sinatra”) would record the English lyrics one year later, where the song would reach number ten on the British music charts.

Picking up the song two years after Monro to create his own version, Sinatra initially recorded the song for use as a single release, along with two other Freeman arrangements on that July day (“Then Suddenly Love” and “Available”). Sinatra must have liked the results, because he would employ Freeman as arranger in several sessions to come. The songs “Forget Domani,” “Somewhere In Your Heart,” “Anytime At All,” and the entirety of Frank’s 1966 “That’s Life” album would be among the work awaiting the arranger in the time to come.

There is a repetitive simplicity in the first three pieces of work Freeman wrote for Sinatra. Overpowering strings, an accompanying musical chorus and heavy drumming dominate the songs. Why Sinatra changed gears to this outlet isn’t hard to understand, because one can never deny Sinatra’s attempts to remain current and viable in the ears of a rapidly changing listening public. His recording of the “Watertown” album in 1969 is perhaps the greatest example of this desire.

One could only think that Sinatra was a bit confronted with the success of his singing pal, Dean Martin. Martin was about to unseat the Beatles at the top of the pop charts with his recording of “Everybody Loves Somebody.” The song, 1940s-vintage, and recorded by dozens of vocalists (Sinatra included) beforehand was recast in a more modern arrangement to great success. The individual behind that Martin session was musician Jimmy Bowen. Meeting with Sinatra not long after, Bowen identified with the Chairman’s desire to incorporate himself into a musical world that was slowly becoming dominated by rock and roll, and would soon sign on as his new producer.

The triumph of the Sinatra tunes “Strangers in the Night” and “That’s Life” were still a few years off, but it would be the influence of Bowen and where he would take the Sinatra camp that would eventually lead to those chart-toppers.

Following the recording of “Softly,” Sinatra asked Bowen what he thought of the results. Bowen replied honestly that he didn’t see the single doing better than number thirty on the charts, but at the least, it would see Sinatra’s voice returning to radio stations. Bowen’s prediction proved nearly correct. The song would reach number twenty-seven on the Billboard Hot 100.

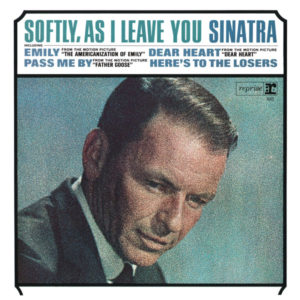

In an effort to collect all of his “single” recordings into one title, “Softly, As I Leave You” would be chosen as the title for his first “pick-up album” for the Reprise label (“Sinatra ’65,” “My Kind of Broadway,” and “Greatest Hits Volumes I & II” would repeat this formula in the five years to follow). The eventual album featured twelve songs, including the three Freeman arrangements.

Frequent Sinatra collaborator Nelson Riddle is also represented on the album, his arrangements of “The Look of Love,” “Dear Heart,” “Come Blow Your Horn,” and “Emily,” dominating the scene. “The Look of Love” was already two years old at this point, released as a single in 1962, while “Come Blow Your Horn” was lifted from the soundtrack of the eponymous Sinatra film of a year before.

“Emily,” the title song from the successful Julie Andrews film “The Americanization of Emily,” is a perfect fit for Sinatra. Complete with a backing chorus and beautiful strings, one only needs to hear this song to see why Riddle and Sinatra had such a good musical relationship over the years. Sinatra and Riddle would record the song again thirteen years later in 1977, in a different musical arrangement, for a “Here’s to The Ladies” album centered around songs of women’s names. Five arrangements would be recorded before the album was cancelled.

Marty Paich is also a credited arranger on this release. The great arranger, perhaps best known for his series of “Dektette” recordings with jazz star Mel Torme throughout the 1950s, contributes both a swing chart (the exciting “Here’s To The Losers) and a lush ballad (the beautiful yet underrated “Love Isn’t Just For The Young”).

Arranger Don Costa, fresh off the success of 1961’s “Sinatra and Strings” and soon to become a frequent collaborator with the Chairman, rounds out the package with his arrangements of “Talk To Me Baby” and “I Can’t Believe I’m Losing You.”

“I Can’t Believe I’m Losing You” is another underrated performance in the Sinatra canon. It was recorded at the tail end of an April 1964 recording session where Sinatra was laying down Nelson Riddle orchestrations for the film “Robin and The Seven Hoods.” With Riddle’s part of the session over, he passed Costa in the hallway outside the studio as Costa was going in to record the single with Frank. Riddle later said it was one of the first times he felt that Sinatra was passing him over in preference to other arrangers. Indeed, with the exception of spaced single releases they would work on through to the late 1970s, the “Strangers in the Night” album of two years later in 1966 would be the last time Sinatra and Riddle would share credits on a full album together.

In May of 1998, shortly after the announcement of Sinatra’s passing, the Sinatra family website, then in its infancy with the rest of the burgeoning World Wide Web, was curtailed to display a memorial to the deceased singer. Many an Internet visitor listening closely to their desktop speakers would hear the gentle sound of “Softly, As I Leave You,” playing in tandem with the screen display.

An honorable use of a song whose lyrics are open to vast interpretation. In terms of the man who sang it, the song is a door to another chapter in the musical life of a legend.

Until next time, Sinatra lovers!

Jerry Pearce is an amateur singer in the vein of Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, and Dick Haymes and has released two discs of standards music, Crossroads in 2010, and One Summer Night in 2016. Samples of his music can be heard on his YouTube Channel. To purchase his CDs use the form box below.

[si-contact-form form=’3′]

July 24th, 2016

July 24th, 2016  CEO

CEO

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: