It’s an unusually balmy late April night here in New Jersey, and as I let the fan in the corner beat cooler air down on me, I’m sitting in front of my record player listening to a disc of master takes from a recording session I was engaged in a few days ago. I don’t qualify as a professional musician in any sense of the word, but having released three albums independently thus far and now working towards a fourth, I’ve always been enamored by the revolution of the recording industry and the technology invented in past years that bring the medium to its current workings. In my thoughts, it reminded me briefly of a fairly forgotten Frank Sinatra album that arrived on stands at the dawn of the 1950s.

As the 1940s gave way to the new decade, by some accounts, Sinatra’s voice was in poor shape and his life was heading into a slump. Pushed out of the top spots in music polls, his cinema career waning, coupled with the premature death of his publicist and a tawdry media scandal that erupted with the revelation of his affair with screen temptress Ava Gardner had left the once great boy singer an emotional wreck. It was the beginning of a nearly three year long nadir in which the man was labeled as poison.

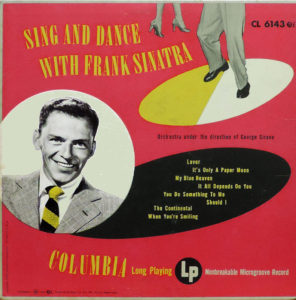

Although his first major recording label, Columbia, would drop him two years later in 1952, the powers that be were reluctant to give up on him at the time. Inspired by some great swinging charts that Sinatra had cut in studio in the midst of the tender romantic ballads he was better known for at the time, producer and veritable clerk of the works Mitch Miller decided to try a new concept with Sinatra: an entire musical package of up-tempo dance tunes. It would be Sinatra’s sixth career record, a collection of four miniature LP records each containing two tunes, comprising eight selections, the form for an extended music program at the time.

Waving his baton before the orchestra was George Siravo, a great and often underrated composer who in later years would become known for his bombastic orchestral arrangements for fellow Hoboken singer Jimmy Roselli. Siravo had orchestrated the bulk of Sinatra’s earlier swing tunes for Columbia and appeared to be the logical choice.

When the sessions kicked off over two dates in April of 1950, Sinatra’s throat was hanging out. Bewildered by the condition of the singer’s voice but desperate to save the session, Miller shut off the power to the microphone recording Sinatra’s vocals and just recorded the band, instructing Sinatra to return when his voice was in better shape. In what would prove to be a harbinger for the dooming times that were to follow, Sinatra walked off stage in the midst of a Copacabana engagement just a few weeks later, when in the midst of struggling with a song, droplets of blood formed at the bottom of his throat. Diagnosed with a hemorrhage of the vocal cords, it would prove to be a major career sideline.

Sometime later, when his voice was recovering, Sinatra met Mitch Miller at the 30th Street studios of Columbia Records late in the night for a clandestine operation. In tow were the completed orchestral arrangements created by Siravo’s orchestra, and together, the two men would work to get Sinatra’s rejuvenated voice onto the arrangements in a process known as “tracking,” which at the time, was considered illegal. Behind a locked door, Sinatra worked into the wee hours of the morning getting his completed, note-perfect vocals in the recordings. When you listen back to the tunes, which include “Lover,” “It’s Only A Paper Moon,” “My Blue Heaven,” and “Should I,” even at the 1950s recording standards, you can hardly tell the difference. The singer was pleased. By using some then unconventional techniques, he created a quality product.

Released that October 1950 on ten-inch LP and the aforementioned four-record set and again in October 1952, the album, “Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra,” wasn’t a smash success, and would prove to be his last full album for Columbia Records, with a handful of singles following. Ironically, the album, in a way, gave listeners a preview of the Sinatra to come, the fedora wearing swingin’ cat that would thrill listeners with his iconic move to Capitol Records in 1953. Siravo would serve as a bookend. While he was the arranger credited for the last Columbia album, he would write seven of the eight arrangements for Sinatra first Capitol release, though the cover would erroneously attribute the entire program to Nelson Riddle.

For someone who has recorded, at this point, four times in a professional recording studio, the idea of tracking being illegal seems almost ridiculous. What once was considered a crime has seemingly become the norm in the music business. The unconventional became a treasured convenience. Many major artists have been known to employ such methods in the execution of recording new songs. Even Sinatra did such in the recordings of the albums “Watertown” and much later on “Duets.”

Each of the four times I was in studio, I recorded my voice to either a pre-recorded instrumentalist, or a full ensemble. My first time behind the microphone in 2010, I blew one line of an important phrase in a song. Distressed, I stopped singing and told the engineer to start the music over again. He gave me a puzzled look and asked me what was wrong. I responded by telling him that I didn’t like the way I sounded on the phrase. He responded by rewinding the track to a point a few lines before, and, pressing a button down on the console, eliminated the vocal I didn’t like and allowed me to insert new ones. I was amazed by that, and the thought occurred to me: if a guy like myself working in a recording studio in New Jersey can do something like that, what are they doing at the big time record labels out on the West Coast? It was the first time that I realized that you can literally be fooled by an artist simply through audio trickery.

Thankfully, I’m happy to say I myself have never benefited from the demon known as “Auto-tune,” but I do feel a bit guilty now that I am among the singers who have become indebted to the technology that has swept through the music medium.

It’s hard to believe that we live in a world where some years ago, a group like Milli Vanilli were being chastised for lip syncing the vocals of other singers, while the same public today cheers on celebrities in a show called “Lip Sync Battle”. The comparison between entertainment like such, and the classic vocalists of yesteryear, well… there is none. And, it leads to idea behind this piece. It’s proof as to why I admire Sinatra and his fellow contemporaries so much. They were more concerned with the quality of a recording rather than making the fast buck with substandard product. All one has to do is remind himself that it took more than twenty full takes of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” in 1955 before Sinatra was satisfied enough with his performance to finally move on.

When the album that “Skin” was on, “Songs For Swingin’ Lovers,” was recorded in the mid-1950s, there were only two receivers catching the action in the studio, one capturing the orchestra, and the other connected to the singer’s microphone. When you’re trying to document things as naturally and organically as possible, there’s very little room for edits and punch-ins. If you’re going to get it right, start over and do the whole thing again.

That’s why I look up to a guy like Frank. Nothing can be perfect, but his performances always come damned close. Whether he was tracking with a faltered voice or doing multiple live takes with a good voice, he was always aiming for that end result of quality.

Perhaps some modern day singers should take those facts into account.

Until next time, Sinatra lovers!

Jerry Pearce is an amateur singer in the vein of Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, and Dick Haymes and has released two discs of standards music, Crossroads in 2010, and One Summer Night in 2016. Samples of his music can be heard on his YouTube Channel. To purchase his CDs use the form box below.

[si-contact-form form=’3′]

May 1st, 2017

May 1st, 2017  CEO

CEO

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: