What if I told you the victims of the biggest mass lynching in American history weren’t Black/African American but Italian immigrants, would you believe it? Well, it’s true. Our nation’s early history reflects a moment in time when “change” that came in the form of immigration was met with resentment and hostility. Every nationality at one point or another has been the target of preconceived notions and bias opinions. This was especially true for migrants of Irish and Italian decent or of Catholic faith. At the time, the common belief was that immigrants would distort or defile the cultural values of America. In addition, all these new arrivals were often seen as unwanted competition in the jobs market. Between 1880 and 1920, more than 20 million foreigners made America their new home. In that decade alone, some 600,000 Italians migrated to America and between 1820 and 1930, some 4.5 million Irish followed.

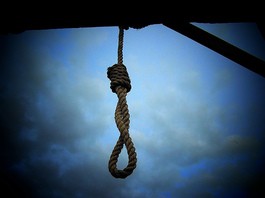

This influx caused a great deal of discord among those who considered themselves to be “natives” here in America and on March 1891 in New Orleans the frustration turned to murder. It all began one evening on October 15, 1890, when police Chief David Hennessy was shot by gunmen as he walked home from work. When help arrived, Hennessy was asked who shot him, supposedly he told officials “Dagoes” (a derogatory term for Italians). Hennessy never revealed any names of any suspects and within several hours of the shooting he died from complications as a resulting of the shooting. Within 24 hours of the shooting over 200 Italian immigrants were rounded up. Local papers quickly blamed the Italian community for the murder.

The trial for the suspects began on February 16, 1891, and concluded on March 13, 1891. The defendants were: Antonio Bagnetto, Joseph P. Macheca, Antonio Marchesi, Bastian Incardona, Gaspare Marchesi( only 14 at the time), Charles Mantranga. At trial, the bulk of the evidence presented was weak or contradictory.

Unfortunately, the murder took place in a bad part of town where the streets were poorly lit making it impossible for witnesses to identify suspects. The officer on the scene who Hennessy reportedly made the “Dago” comment to, Captain Bill O’Connor, didn’t testify and there were numerous other discrepancies as well. Despite the prosecution attempt to eliminate anyone with an Italian background from the jury and only selecting jurors who believed in the death penalty all the defendants were found “Not Guilty” with the exception of Pietro Monasterio, Emmanuele Polizzi, and Antonio Scaffidi their case ended in a mistrial. For whatever reason, the men were still detained after the trial.

When the vigilantes arrived, screaming and shouting obscenities, the men were released by the guard from their cells in an attempt to hide. Despite their best efforts, Antonio Bagnetto, James Caruso, Loretto Comitz, Rocco Geraci, Joseph P. Macheca, Antonio Marchesi, Pietro Monasterio, Emmanuele Polizzi, Frank Romero, Antonio Scaffidi, and Charles Traina were all lynched, along with other atrocities.

In the wake of the hanging, Teddy Roosevelt (not yet president) famously said they were “a rather good thing”, referring to the lynching’s. A March 16, 1891, editorial by The New York Times referred to the victims of the lynching’s as “… sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins.” John Parker, who helped organize the lynch mob, later went on to be governor of Louisiana. In 1911, he said Italians were “just a little worse than the Negro, being if anything filthier in [their] habits, lawless, and treacherous’.

In Richard Gambino’s book Vendetta: The True Story of the Largest Lynching in US History, my source for this article and a really good read, does a good job at explaining why this incident was the largest mass lynching by definition. For those still in disbelief, Gambino’s explanation simplifies definitively. By definition “as measured by the number of people illegally killed in one place at one time, the victims’ identities predetermined for some specific alleged offense.”

This classification would not include massacres, such as the Chinese massacre of 1871, in which victims are chosen “without regard to their individual identities and in which no specific offense on their part is alleged. I found this event interesting because of the abnormalities and to some extent, for me, it justified why some became a part of Costra Nostra- protection. The travesty of this event is different from the norm and the aftermath was simply grievous. To think, these men who came here in hopes of a better life and were murdered out of ignorance and those who were in a position to set the standard perpetuated the situation by condoning the violence.

[si-contact-form form=’3′]

July 20th, 2017

July 20th, 2017  CEO

CEO

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: